Cannot Access to Remedy

Wali works in New York City to support his family in Senegal. He delivers food for a living.

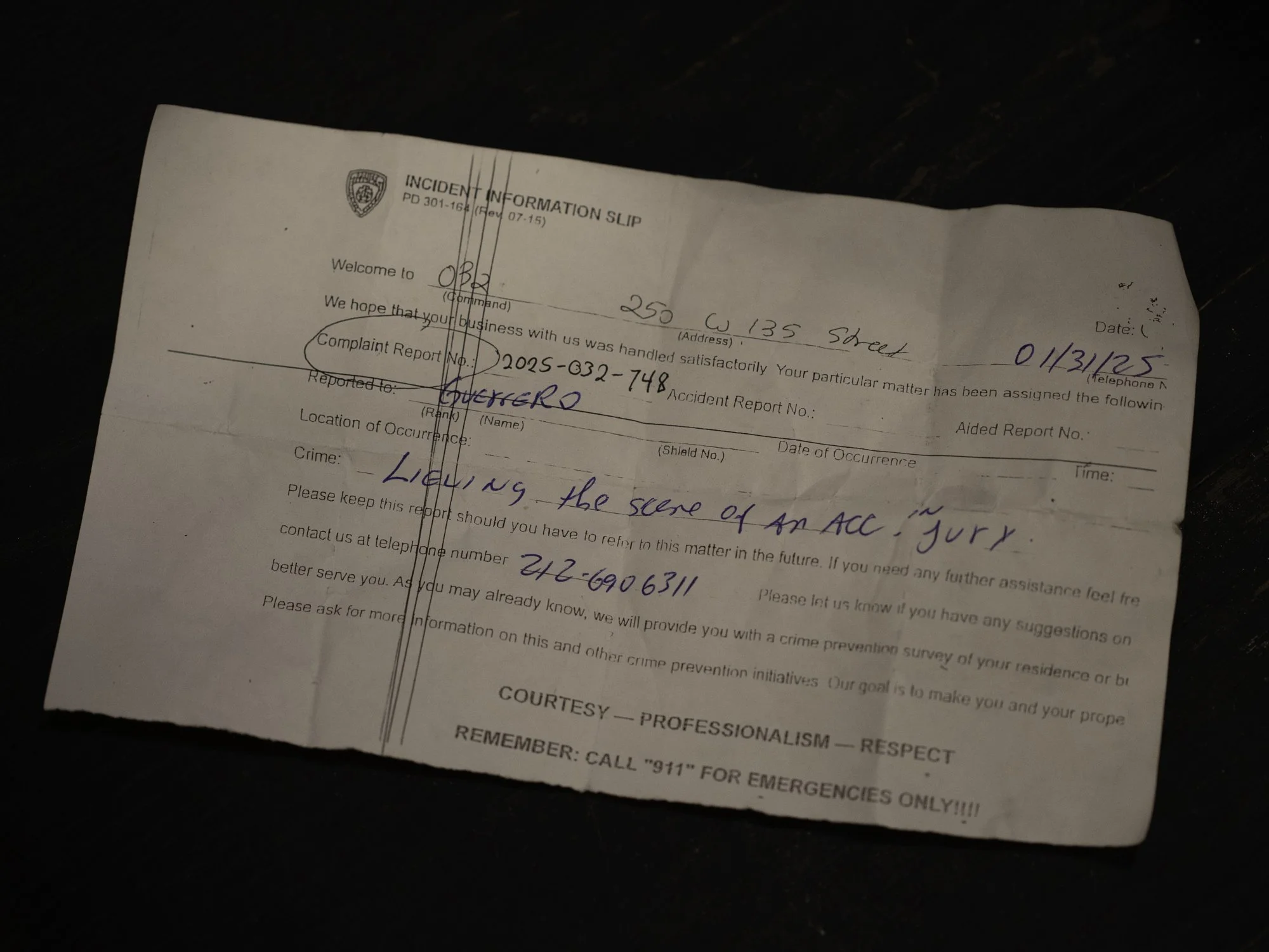

One rainy Friday, while he was on a delivery, a car hit him. He fainted and woke up inside an ambulance. His shoulder was badly swollen and painful. To have his medical bills covered, he needed an official accident report from the New York Police Department (NYPD).

But even after visiting the police station about six times, he couldn’t get the right report. The police had recorded his case as property damage instead of personal injury. When he asked them to correct it, they were reluctant to review the surveillance cameras or share information about the driver who hit him. Frustrated and confused by the system, Wali eventually gave up.

Wali’s case illustrates how both the state and businesses can fail to uphold human rights protections. Under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), the international framework for preventing and addressing abuses linked to business activity , victims of human rights violations must have effective access to remedy. These remedies, whether judicial or non-judicial, should be legitimate, accessible, equitable, transparent, and prompt.

In Wali’s situation, the judicial remedy failed at the first step: obtaining an accurate police report. On the corporate side, the delivery platform (DoorDash) provides an online reporting system for injured workers, but it is only in English, a language Wali does not read.

As a non-citizen worker, Wali finds himself in a gap between legal systems. Yet according to the UNGPs, states have an obligation to provide judicial remedies even for non-citizens, and companies are equally responsible for ensuring non-judicial remedies are accessible and fair.